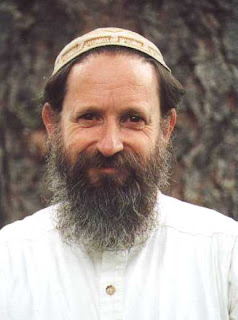

Today I have learned of the untimely passing of Rabbi David Zeller, a grand soul of spirit and vision. May his family find comfort among the mourners for Jerusalem. I dedicate this to him and his students.

There was a profoundly touching program last evening on "Talk of The Nation" on NPR. The guest author wrote about a man blinded at an early age by an accident. This man had been offered restoration of his sight through a breakthrough medical procedure. The man risked cancer and even death through this surgery and the drugs that would be necessary retain his vision. It was in line with the ethical conundra presented on my undergraduate public policy final exam. In short that test posed an essay question of how to institute control (public or private) over a hypothetical machine which could transport an individual over massive distances in a split second. In the fantasy scenario, the machine made a piercing screech every time it was used which would instantly render deaf, anyone within a hundred mile radius. I loved the question. I believe that I wrote an argument for public control over the device, and further advocated to have it permanently dismantled.

The benefits to a person suddenly given sight after many years blind, were to me at least quite evident; to finally know the green of a forest, to explore the work of Van Gogh, Rothko, and Vermeer. To hear the sun with ones eyes. Images. I am numb at the potential for eternal rediscovery. The author on last night's program did much research into the little known area of people "cured" of their blindness. Apparently there are no more than 20 such recorded cases dating back to antiquity. In so many cases the result for the patient was the same; despondency, depression and even self mutilation. It appears that the brain grows accustomed to the means and the signals which it is given to perceive and make sense of the landscape around it, even if those messages are, at least to us in the sighted community, clearly and obviously diminished when one is blind or otherwise afferently incapacitated. The deaf learn to read lips and grow ultra-sensitive to vibrations. The blind can know the presence of a friend just by her footsteps or from the mix of sweat and perfume. What a gift I thought to be granted a new pallette with which to enjoy and understand the world. But instead it seems that a life spent learning through alternative means, magnifying and developing abilities as variants to the damaged sensory receptor, is not only a compensatory set of responses, but may indeed be simply natural.

The brain is not only a computer that stores and recalls events, people, or sensations. Yes, its job is to help us learn and identify the difference between the likes of fur and sandpaper, of course. However it is also a creative universe of buried and dormant lenses. I've heard musicians and writers go as far as to say that they cannot be responsible for their creations; that they tune in on something, and become the conduit for that thing. It is as if they are mute and rigid ducts through which an understanding or influx of meaning can flow from one dimension to the next. Nice idea, especially if their art either stinks or really angers a whole lot of people. Not to digress really, because the converse of that affective response to their role in society communicates a singular and important humility. I had an art professor who once said, "in this painting, you can see the artist smiling." Some sort of pure heroine-like substance flushes my brain when I even consider that state of creativity. Click, brightness, nirvana.

The brain is also a cognitive tool that seeks to make connections from what it knows to what it now sees, and I use the latter sense as a metaphor for all senses. The blind person with newly restored sight can in fact be granted better than 20/20 vision. Amazing. It is said that his perception of color and movement is more crisp and vivid than for those with unfettered and perfect vision all their lives. Yet there is a down-side associated with the gift. Apparently for those of us in the sighted community, our ability to discern the subtleties involved in relationships concern a lifetime of studying and interpreting facial expressions. It's a secondhand skill for the majority. Those with newly restored sight often cannot make sense of the human face. It is an enigma, a puzzle; a new form of blindness with which the patient now must contend. Context is broken and an alien set of stimuli need to be assimilated, if possible. And it's not always possible. Suicide is a very real and not uncommon outcome.

This reminds me of the story of four scholars who enter the proverbial "Pardes," (Hebrew for grove) an allegory for new meaning, the Garden of Eden, knowledge of the eternal. In this story, one sage dies upon his encounter. Another scholar becomes an apostate, and yet a third goes mad. The last one exits with the mission to open an academy of learning. Those who learn the mystical texts and discover the science and the supernal wonder of the infinite gain one, if not a million profound insights, among which is the realization that the more one knows, the less one really knows. With true knowledge also comes a humility, not just a smack across the wet nose to the uninitiated, or an impatience born of exile in an ivory tower. To know that world is to know this world more. To see the presence of God on that side, is to see her all the more on our side. To the blind, being granted "sight" can be an overwhelming, maddening, and frightening prospect. For others it is a charge to untie a difficult knot. Imagine having all that you know, all that with which you find comfort and routine, summarily moved aside - even just a bit. You would face a terrifying unfamiliarity. You would be as one could say, deaf, dumb and blind. We're on our own, cousin.